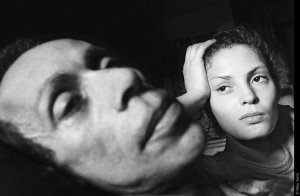

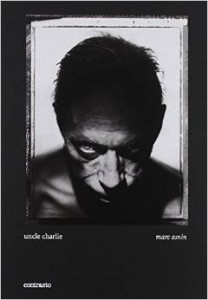

Marc Asnin - Uncle Charlie

Uncle Charlie says he never had a friend. That no one listened then, and no one listens now. After thirty years of photographing him, I am the last guy standing, the only constant in Charlie’s life.

My uncle was born into dysfunction and he bred dysfunction throughout his life. Much like his father, Uncle Charlie has ended up by the window, a shell of himself, looking out onto a world that never had a place for him, waiting for a chance that didn’t come. But he survived. Through it all, he survived. And no one can take that away from him.

People often ask me what Uncle Charlie is about. After thirty years, one would think I would be able to easily sum it up. But this book is life, raw unintelligible life; the life of one man, my uncle, and as in life, there are no easy answers or summaries. It’s about broken dreams, disappointment, and having the resiliency to find slivers of happiness in an oppressed existence. It’s about consequences, missed opportunities, delusions and loss. It’s about having the guts to look intensely at the familiar and process what’s in front of you, taking an account of your family, your society and what is said about both. It’s about a relationship between two men, from two generations, living very different lives, bound by family. It’s a collaboration of sorts: his words and my images. It’s my dance with my godfather.

I am not the first guy to document his family. But for me, both the subject and my imagery reflect who I am. The images are intimate and confrontational. They are unapologetic, yet empathetic. When the subject is your only family, the consequences are inescapable. My cousins have made it clear they want nothing to do with me any longer. Uncle Charlie is my mother’s brother and my godfather. As this process together comes to a close, he assures me he will see me in hell for what I’ve done. But with my uncle, nothing is forever and life is never walked in a straight line. This project is simultaneously an intimate documentation and the source of my separation from my family. Ironically enough, after more than thirty years, I now find myself on the outside looking in.

I am not the first guy to document his family. But for me, both the subject and my imagery reflect who I am. The images are intimate and confrontational. They are unapologetic, yet empathetic. When the subject is your only family, the consequences are inescapable. My cousins have made it clear they want nothing to do with me any longer. Uncle Charlie is my mother’s brother and my godfather. As this process together comes to a close, he assures me he will see me in hell for what I’ve done. But with my uncle, nothing is forever and life is never walked in a straight line. This project is simultaneously an intimate documentation and the source of my separation from my family. Ironically enough, after more than thirty years, I now find myself on the outside looking in.

When I look back on all the time I spent with my family, I wonder about the different roles that I played. Was I primarily the documentarian, his nephew, their cousin, or just the only one who listened? I’m sure I was all of these at different times.

To be ignored in life and eventually forgotten in death is a terrible thing. I think this book has given my uncle the dignity to tell his own story in his own words, a chance to step up onto an imaginary stage before an anonymous audience and be heard. He has always considered his life an untold tragedy, at times comparing it to Hiroshima. He got the chance he always wanted: to be heard. In exchange, the world also gets the chance to look back in through the window that Charlie sits by everyday and see what’s on the other side.

I’m still wondering who I am in my Uncle Charlie’s life. Did my mother give him his only friend in the world? Why did Charlie choose to share his life with me? Maybe all these questions I have to carry with me have no answers. Maybe this hope for understanding my uncle is my “Godot”.

Link: Uncle Charlie book: www.unclecharliebook.comMarc Asnin

Marc Asnin is a renowned documentary photographer, having been published in numerous publications including Life, Fortune, The New Yorker, The New York Times Sunday Magazine, French Geo, La Repubblica, Le Monde, and Stern.

His work has been exhibited in museums and galleries in the United States and Europe, including the MOMA, Baltimore Museum of Art, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Steve Kasher Gallery, Blue Sky Gallery and is also included in several permanent collections, including the National Museum of American Art, the International Center of Photography, the Museum of the City of New York, the Portland Museum of Art, the Zimmerli Art Museum and the Schomburg Center.

His work has received numerous accolades, most notably the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, and the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Mother Jones Fund for Documentary Photography Grant, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the Alicia Patterson Fellowship.

Asnin’s work has appeared in books such as Uncle Charlie (Contrasto 2012), The New York Times Magazine Photographs (Aperture 2011), After Weegee (Syracuse University Press 2011), New York 400 (Running Press, 2009), Blink (Phaidon Press, 1994), Flesh & Blood (Picture Project 1992).

Personal website: www.marcasnin.com

Marc Asnin has recently launched an international photography campaign against the death penalty, named Selfie Against the Death Penalty.